Before Kaslo was a rollicking boom town…

George Thomas Kane came to the delta and was much impressed by the beauty of the site and its possible value as a location for a town. This was in 1887. He had been sent to the Kootenays by the Waterous Engine Works of Brantford, Ontario to install machinery in a sawmill at Canal Flats.

In 1890 Kane applied for a preemption on the shore front and sent for his brother David to live there while he went to the coast to organize the Kaslo-Kootenay Land Company. David Kane built a log cabin near what is now Front and Third Streets. He lived there alone all that summer with his small dog, living off the stores he had brought and berries and fish. He and his dog befriended a curious bear cub, which you can see on the roof in the photo below. In later years the bear used to amble down to shore to greet the newcomers who soon were arriving daily in all manner of boats. (The bear’s story did not end well, since it developed an unfortunate appetite for small dogs.)

A year before Kane’s application for a pre-emption, sawmill owner George Buchanan had staked a timber claim but he did not stay. In 1891 he returned, this time with his wife. They shared breakfast with David Kane at his log cabin. Kane’s clearing gang for the new townsite was already there. 160 acres had been set aside for the townsite and surveyor John Keen had laid out the streets and the lots. Land that only months before had been covered in heavy timber was being sold in short order at fabulous prices for the more choice building lots. Men came from all over Canada and the US, the largest number arriving via Bonner’s Ferry from Spokane and Coeur d’Alene.

Although Kaslo was still a settlement of tents and cabins, the first permanent buildings began to make their appearance. The first frame house was completed in 1891; the first home in Kaslo for the Kane family. They came all the way from Eastern Canada – by train to Spokane, then by stage coach to Bonner’s Ferry. The last leg of the trip was on-board a wood-burning tug. They pulled up to the newly built wharf in Kaslo in a cloud of smoke that smelled strongly of burning ham – because the tug had run out of wood and, rather than lose power on the lake, the captain had resorted to burning a few hams to be sure to make landfall.

In May of 1892, the population of Kaslo was about 600, mostly men, and mainly miners and prospectors. The first sternwheelers arrived, loaded to capacity with people and supplies and nine miles of the Kaslo-Slocan trail had already been completed. Marsh Adams was the name of Kaslo’s first policeman. By all accounts the one man police force was very successful in keeping law and order. But the spring of 1893 the population ballooned to 3,000 – there were 20 saloons and the Theatre Comique on A Avenue employed 80 ladies (known locally as “boxrustlers”), and operated a saloon on each of its three levels. That’s when Marsh Adams got himself a constable.

The Fire of 1894

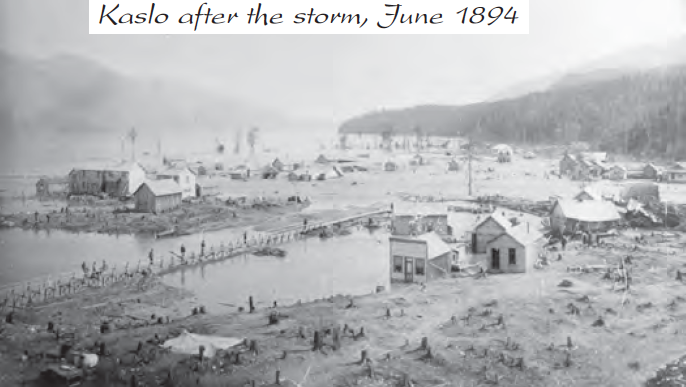

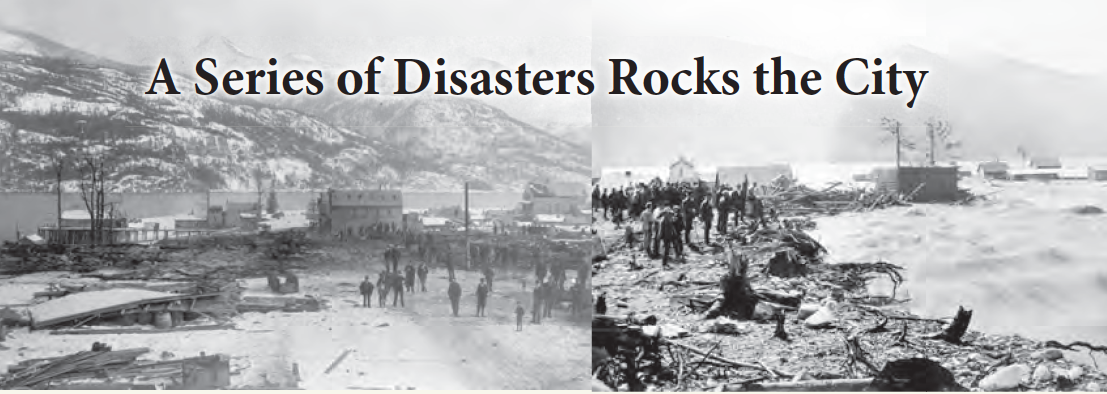

Kaslo’s first full year as a city must have felt like the end. In February 1894 a fire destroyed almost an entire block of Front Street. And four months later almost half of the town was flooded.

Kaslo’s first full year as a city must have felt like the end. In February 1894 a fire destroyed almost an entire block of Front Street. And four months later almost half of the town was flooded.

The fire alarm sounded at 2:30 am. When the volunteer fire brigade responded, they found a large blaze at the Bon Ton Restaurant on Front Street. In the five weeks previous to this, three attempts had been made to destroy the town by fire. The citizens had been living in daily fear of firebugs and the City had hired a night watchman in an attempt to prevent further conflagrations.

In spite of the efforts of the firemen and practically every able bodied man in town, the fire spread rapidly, and both sides of the street were burning. A bucket brigade was formed down to the lake at the end of Front Street. Blankets were soaked with water and spread over roofs of nearby buildings. Merchandise of every description was hurriedly removed from hotels, saloons and stores in the path of the fire. This was put into huge piles in the snow, covered with blankets, carpets or mattresses and soaked with water.

A light snow was falling and it was bitterly cold. The clothing of the firefighters was caked with ice. It soon became apparent that desperate measures were necessary. At about 4:30 am, a group of men made preparations to blow up Byer’s Hardware store, which was directly in the path of the fire. A case of dynamite was suspended by a rope from the ceiling and a fuse attached to it. The store blew up with such a terrific explosion it shattered most of the glass of the surrounding buildings. Several smaller buildings were hastily pulled down and the clear space checked the fire for the first time. A few people were slightly injured by flying glass and some slight burns were suffered but there were no other casualties.

While practically every man in Kaslo fought the fire all night, some found time to sample the “merchandise” which the various saloon owners had stacked out in the street to prevent it from being burned. Next morning, some of the teamsters needed a little assistance before they could mount to the driver’s seat of the ore-wagons.

A Cyclones Devastating Work

The weather was close and hot, unusually so for early June. All day Saturday the water in Kootenay Lake continued to rise, and by six o’clock it was 15 inches higher than on the previous evening.

Sunday dawned exceedingly warm and by ten o’clock it had become oppressively hot, continuing so until afternoon. The water of the lake was as smooth as a mill pond, and many took to small watercraft, some to row among the submerged buildings and others to visit more distant points of interest.

The water kept on encroaching and was starting to inundate Third Street. Kaslo River was pouring an immense volume of muddy water down its main channel, and there were two subsidiary channels of no small proportions. Not infrequently large trees were brought down with a force that seemed irresistible. In many of the buildings the water reached to the tops of the windows. Way down the lake towards the southeast, heavy clouds came nearer and nearer, and fitful gusts of hot wind indicated that a storm of unusual severity was approaching. Soon the wind increased to a hurricane, and then to a veritable cyclone. The lake was lashed into a perfect fury. Huge waves of oceanic magnitude rolled in, wreaking havoc. On land the air was gritty with dust and sand and small stones flew though the air rattling against the buildings like volleys of rifle bullets.

When the force of the gale was spent, and people were able to take stock of the damage, not a building remained intact east of Third and north of the Kaslo River, and all but four or five had been utterly destroyed.

The depths of Kaslo’s loss had, however not yet been sounded. Downwards towards the lake came the fierce torrent of Kaslo River, having busted though a log jam upriver. About two o’clock on Monday morning the water was fl owing over the deck of the Third Street bridge, and an immense tree with roots and branches attached had lodged against it. Soon another tree came barrelling down and struck a tremendous blow. The wooden bridge broke in the centre and its two halves were taken by the swift current, carried out to the lake where they sank.

By 1891, Ainsworth was Booming

By 1891, Ainsworth, south of Kaslo, was booming. The mines were producing rich lead ore (galena) and silver too. Supplies and equipment were arriving daily along with prospectors eager to get out into the hills and have their dreams fulfilled. The area over the mountains to the west and northwest of Ainsworth was considered to be all granitic type rocks and, as such would be devoid of any commercial mineralization. It was “shunned by prospectors who had an unwarranted lack of faith in the likelihood of veins being in this formation.”

In August 1891, Andrew Jardine showed up in Ainsworth with a quantity of highgrade silver-lead ore. On the value being ascertained, a stampede for the neighbourhood of the new find was a natural result. Prospectors swarmed the Blue Ridge Mountains, 13 miles Westerly from Kaslo, and many fairly good discoveries were made.

Early in September 1891, the Payne mine was located, the first actual mine in the Slocan District. 140 claims were located before the end of the year.

Residents of Kootenay Lake at once began making trails to the Slocan. An effort was made to get the Government to build a wagon road from Nakusp to the head of Slocan Lake to move supplies into the Slocan claims and the ore out, but the Government refused. The residents of Kaslo then induced the Slocan miners to transfer their pack animals from the Nakusp trail to the Kaslo trail. Before the winter was over the road was passable by wagons and then sleighs. Over this road hundreds of tons of high-grade ore were transported during the winter of 1892-93. All supplies had to be carried up to the mine site by horses. Rawhiding the ore out in winter was cheaper than packing it out in the summer. There were occasions when the horses had to be fitted with snowshoes.

Some mines were found by accident and others by hard work. “After many hardships and disappointments, but after persistent prospecting, the Ruth Vein was accidentally disclosed by a small piece or two of iron stained rock sticking in the roots of a windfallen tree… In this case a vein was eventually determined to have been the richest ore chute ever mined in the Slocan.”

Some mines were found by accident and others by hard work. “After many hardships and disappointments, but after persistent prospecting, the Ruth Vein was accidentally disclosed by a small piece or two of iron stained rock sticking in the roots of a windfallen tree… In this case a vein was eventually determined to have been the richest ore chute ever mined in the Slocan.”

The first two or three years all mining was done by hand. It has been said single-jacking is what made the country. Single-jacking is a term used to indicate one man working alone with a drill steel and a hammer. Double jacking is a two man team – one man holding, turned the steel after each blow of the hammer. It was turned 8, 10, 9 or 12 times to the circle. If it was turned too much the steel would bounce, so the rate of turn had to be slowed down.

Andy Jardine, Jack (Lardo) McDonald and Jack Allen (the Beaver Group) had staked a number of claims. Their camp was known asJardine’s Camp. Beaver was the name of the claim that had precipitated so much mining frenzy. In 1893 it was reported “These claims are being developed by tunnels, but so far no ore has been shipped.” In 1919: “The Beaver was worked for about 3 months by the owners, extending the tunnel 35 feet, with encouraging improvement of the ore showing.” But the Beaver never became a producing mine. The stampede it triggered, on the other hand, led to discoveries which to date, have produced metals to the value of almost $350,000,000.

Railways and Roads

The Kaslo and Sandon (K&S) Railway was incorporated in 1892, a year before Kaslo became a City. The province granted a charter to Alex Ewen, DJ Munn and John Hendry of New Westminster for all that was required to get a railway from Kaslo west to the mines above Carpenter and Sandon creeks and those lying near the head waters of Bear Creek. 10,240 acres of land would be granted (land that the grantees could sell) per mile of completed railway. That’s how infrastructure was financed in those days.

In the summer of ’93 the price of silver crashed and the owners were permitted to amend the charter to build a narrow gauge railway, a significant economy. Tracks that are closer together mean smaller trains – and smaller trains require shallower cuts, and the rolling stock can get around curves that larger trains cannot. A nimbler train, just like a packhorse vs a wagon and team, can make progress on the skimpiest of routes.

On May 8th of 1895, the grading of a right-of-way up the Kaslo River began. Through terrain which is some of the most savagely hostile to railroading on the planet, a track of 45-pound rail was pounded up 3.25% grades to the 1,700 foot level at Zincton. On a fragile looking “grass hopper” trestle, chief construction engineer W.F. Tye inched the line across the brow of Payne’s Bluff, 1,000 feet above the valley floor. Less than 29 miles from Kaslo, the K&S reached Sandon on October 22nd. Rich ores from the Bonanza King, the Noble Five and the Eureka joined those of the Goodenough, the Payne, the Rambler-Cariboo and the Slocan Star on their way to market.

There was, however, a costly bottleneck in the K&S’s operation. Because they were not of standard gauge, the ore cars of the K&S could not simply be run onto barges and off-loaded onto the rails of the Great Northern. In a laborious, time-consuming process, ore was dumped onto the docks at Kaslo and wheelbarrowed aboard ships. At Bonner’s Ferry the process had to be reversed. When the line was sold to a Kaslo syndicate, partner Daniel Munn remarked “T’was a perverse child with us and its career will always be interesting.”

Truer words were never spoken. In 1910 a wildfire destroyed the tracks from Rossiter Creek to Sandon. In 1912 the crippled K&S line and rolling stock was bought out by the Canadian Pacific Railway. By 1950 only one mixed passenger/ freight train was running just once a week between Kaslo and Nakusp.

Five years later, torrential rains caused Carpenter Creek to flood and burst its banks. Most of downtown Sandon and its main street collapsed into the creek and was carried away, taking the trestles and creek side grade of the CPR with it. The CPR made no attempt to rebuild the line and for many years, end of track was near a spectacular washout with rails still dangling a hundred feet above Carpenter Creek.

Wagon Road

In 1891, when silver was discovered in the Kaslo River valley, prospectors rushed to stake their claims. The Kaslo Board of Trade initiated the work of building a proper road and by the winter of 1892/3 the wagon road was “fit for sleighing.” The Kaslo Transportation Co. had stages running daily to Bear Lake, one leaving Kaslo at 7am and another leaving from Bear Lake at 8am. Horses and wagons, stage coaches, and pack trains carved pocks and dug ruts as wranglers pushed and pulled their loads over the new road. By 1923, the road was handling gasoline- powered vehicles.

The Wagon Road was made obsolete in the 1960s when Highway 31A was constructed, a highway that stayed close to Kaslo River for most of its length, following the route of the rail bed of the old K&S railway. In 1993 the community of Kaslo and the Rails to Trails Society began the restoration of the Wagon Road as a multi-purpose recreation trail, complete with interpretive signs illustrating the history of the area.

By Road, South and North

A road was finally completed, linking Balfour to Kaslo. By 1926 one could drive all the way to Nelson, a trip that formerly could only be made by boat.

The road north opened up in 1955 but it was pretty rough. In order to get to the school bus on time, Meadow Creek teenagers had to get up at 5:30 in the morning. Before the road was built, Kaslo folks like Edie Allen took in the high school students who lived up the lake. They’d stay at least Monday to Friday, sometimes not returning home for weeks at a time.

After Kaslo’s flood in 1894, some residents found that they had not only lost their houses, but their land too had been torn away by the raging river. It was cheaper to buy land up the hill which was still undeveloped. The road was busy and rutted, being the main supply road to Sandon and the mines west. of Kaslo. In 1898 a trestle bridge was constructed which went over the K&S tracks, a great improvement.

A Sawmill Town

It was in 1889 that G.O. Buchanan drove a stake into the ground, just above the bay, in what is now Kaslo. The stake was a notice of his application for a timber claim that extended one and a half miles west and one mile south – about 960 acres. There was a huge demand for timber. The railways swallowed up acres of forestland for ties, even the pack roads and the wagon roads needed timbers for traction through the muck (these sections were called “corduroy” roads.) And of course, the precipitous growth of population in boom towns like Kaslo meant houses and all manner of commercial buildings were being built as fast as the wood and labour could be secured. By 1893 Buchanan’s hastily built sawmill in Kaslo Bay was running night and day.

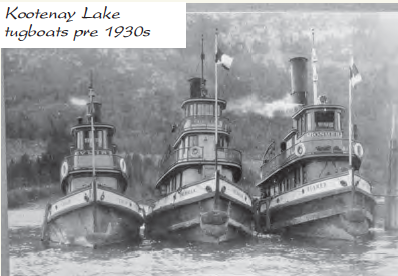

During the war years (1939-1945) many Kaslo men worked in timber operations for Kootenay Lake Forest Products, a Nelson mill.  The cottonwoods which grew to a massive size in the low lying areas at the north end of the lake became the plywood sheeting for the barracks of Canada’s armed forces. The massive trunks were floated from the flats at the head of Kootenay Lake, then at Lardeau were loaded onto barges fitted out with railway flatdeck cars. Since there was no through road or railway track between Kaslo and Lardeau, the lake was the only highway. The barges would then be pushed by the SS Moyie sternwheeler or pulled by tugboat to Kaslo. Just below where the Kaslo Hotel is now, the loaded rail cars would get transferred from the barge and coupled to the locomotive on the CPR Line to Sandon & Nakusp.

The cottonwoods which grew to a massive size in the low lying areas at the north end of the lake became the plywood sheeting for the barracks of Canada’s armed forces. The massive trunks were floated from the flats at the head of Kootenay Lake, then at Lardeau were loaded onto barges fitted out with railway flatdeck cars. Since there was no through road or railway track between Kaslo and Lardeau, the lake was the only highway. The barges would then be pushed by the SS Moyie sternwheeler or pulled by tugboat to Kaslo. Just below where the Kaslo Hotel is now, the loaded rail cars would get transferred from the barge and coupled to the locomotive on the CPR Line to Sandon & Nakusp.

Or logs would go straight into the lake. It was a dangerous job containing them into booms with the heavy iron chains. Tug boats pulled the log booms, either to the train at Kaslo or all the way to Nelson.

When Kaslo’s T&H Sawmill started logging across the lake, the mill was moved from its site on Arena Avenue to the Kaslo River mouth. The timber from Deer Creek was towed across the lake to the mill on the beach in booms. Hopping around on the great floating raft of logs tethered at the mill site was a forbidden activity that attracted the more daredevil teenagers in Kaslo at the time.

T&H sawmill was, for a time, Kaslo’s biggest employer, but it suffered a disastrous fire in October, 1971 – about 60 men were out of a job the next day. (T&H re-tooled and stayed in business until 1983.) Other local mills during the 1950s and ‘60s included Chernoff’s mill, south of the golf course, and there was once a mill near where the airport is now. The Aldinger brothers’ first mill was on family land where Bjerkness Creek crosses the Back Road. The brothers Ed, Fred and Horst later were to establish the mill at Cooper Creek, which became Meadow Creek Cedar.

Around 1990 the Aldingers sold the mill, which, as the name suggests, was designed to mill old growth cedar, to a Japanese concern. The mill was reconfigured to mill Douglas Fir and was a major area employer until it was sold again in 2005. After that employment at the mill was spotty and uncertain, reflecting the variability in the new management schemes initiated by the owner who lived in the lower mainland. In 2013 a fi re destroyed much of the milling equipment and it has not been rebuilt.

Timber claims and stumpage?

As early as 1884 when the BC government enacted the Timber Act, loggers were required to pay a tax on the volume of timber they removed from Crown land. In 1889 G.O. Buchanan had to stake a timber claim, which granted him exclusive rights to all the timber in the area he applied for, but he was not granted ownership of the land.

With the development of the BC forest service (est. 1912), management areas were mapped and timber sales were advertised. Mills and logging companies would be invited to bid on the patch of timber laid out by the government foresters. But purchasing the right to cut down timber, in the middle part of the 20th century could be as simple as applying for a “Limit.” If you found a nice patch of timber, and it wasn’t allocated to anyone else, the forest service would allow you to cut it and market it – of course you were charged a fee based on the number of board feet (a “board foot” is 12 x 12 inches x 1 inch thick) – a tax that was (is) called “stumpage.”

Kaslo area timber claims were non-replaceable rights until 2006 when the Kaslo Community Forest Society (est. 1995) was granted an area-based tenure, giving it more flexibility but also much more accountability for the long-term viability of the forestlands under its stewardship. The community forest also has a recreation tenure – the Buchanan Recreation Area, locally known as “Bucky” – which is located on the lower slopes of Mt Buchanan, just west of Kaslo.

Fruit Farming & Tourism

One of Kaslo’s early industries, after mining and logging and all the services required to support those, was fruit ranching. The virgin forest in the western part of town and halfway up the hill to Shutty Bench was cleared and stumped. Apple trees – especially Gravenstein – and Bing and Lambert cherry trees were planted and the Kaslo Fruit Growers Association was formed by Mr. J.W. Cockle. The Kaslo Fruit Fair was the outstanding event of its kind in the BC Interior. Kaslo cherries won first prize in London, England in 1909 and Kaslo apples won first prize at the Fruit Exhibition in Chicago in 1912. You could say that Kaslo fruit was world famous.

One of Kaslo’s early industries, after mining and logging and all the services required to support those, was fruit ranching. The virgin forest in the western part of town and halfway up the hill to Shutty Bench was cleared and stumped. Apple trees – especially Gravenstein – and Bing and Lambert cherry trees were planted and the Kaslo Fruit Growers Association was formed by Mr. J.W. Cockle. The Kaslo Fruit Fair was the outstanding event of its kind in the BC Interior. Kaslo cherries won first prize in London, England in 1909 and Kaslo apples won first prize at the Fruit Exhibition in Chicago in 1912. You could say that Kaslo fruit was world famous.

In 1932, the City Council decided it would be an excellent idea to plant cherry trees instead of shade trees along the boulevards in lower Kaslo. There is still one on B Avenue below Third Street. In a reversal almost a century later, Kaslo Village council decided that free cherries for bears was not in the best interest of the townspeople and that all new trees planted by the municipality would be strictly ornamental shade trees.

Depending on the decade, tourism has played a more or less important part in Kaslo’s economy since almost the beginning. An early piece on the charms of Kaslo as a tourist destination is at right.

Kaslo Fruit Fair, 1912

The weather being in a reasonable mood, the 6th Annual Kootenay Lake Fruit Fair passed off very nicely indeed. The Exhibition was fully up to expectations in every way.… Rowland Hunt, MP for South Shropshire, England formally declared the fair open. Mr Hunt stated that he was delighted and felt honored in having the privilege of saying a few words to the people of Kaslo upon the occasion. He had no hesitation in saying that nowhere had he seen such splendid fruit as was on exhibition in the hall where he was speaking. “Where I live in the Old Country, there is nothing to approach it,” he said, “and I would advise the ranchers here to strive for the old country market, where there is always a demand for high class fruit such as is produced in the great Kootenay country…

The Kootenaiian 1912

Cherries Roll to Market (but…)

For the past two weeks the Kaslo Motor Transport big freight lorries have been making special night trips to Nelson with Kaslo’s cherry harvest…

Many of the larger growers report a large percentage of splits especially on the Bench and up the Hill. But many orchards in town and at Mirror Lake have an average size crop of lovely fruit and these tons of cherries will be welcome on the Canadian market this year, especially after the shortage from split elsewhere, and from flood failure.

One thing is encouraging. There is little sign of little cherry damage in this year’s crop and growers are hoping the plague is on the wane. So far no help from the scientists, who still have no method of control to offer except to cut out the tree.

The Kootenaiian 1948

From the Lethbridge Herald, 1921

Tucked away in a corner of the Kootenays lies the tiny village of Kaslo which has only of recent years been discovered by prairie folk. Making one more stage from Procter and Nelson, which have been highly popular of late, Kaslo is now being “done.”

The remnant of a prosperous mining centre of 10,000 (sic), Kaslo bears a history. All about are evidences of past and prosperous days that have slackened into the dull monotony of the sunset of life.

Days of revelry have changed into the tamer pleasures of the summer resort. The prospectors, lured into the mountains by the search of adventure and wealth, appear no more. The little main street that once held 24 noisy dance halls, bustles only with the steps of a few tourist shoppers. …

Kaslo –“The Place of Many Berries”– so the Indians called it. And truly it is well named for the great wild saskatoons hang luxuriously; the pink-eyed salmon berries stare out at every turn; the bold huckleberries swell with pride at their prolificity. Cultivated fruits abound too, and “The Place of Many Berries” has become famous for its cherries and its apples.

All the attractions of the better known and more professional resorts are here – mountain climbing, boating, camping, fishing, swimming, fruits. There is a beach with wonderful prospects, but at present it is impaired by past history, for, if one may read the signs aright, it has been used as the city dumping ground, with the result that many a small voice runs screaming home with gashes made by ugly broken bottles or tin cans. Here is great work for one of the public- minded organizations of the little town, now depleted in population to about 900 souls. …

Lethbridge Herald 1921

A Sporting Town

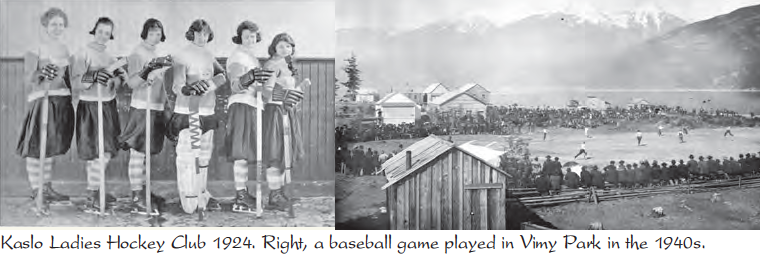

The Sporting Life It’s no surprise that sports of all kinds were popular in Kaslo from the start. Loungers were not likely to undertake the arduous trip into Kootenay Country. The founders of Kaslo were ambitious, mostly fit, and unafraid of physical risk. Miners, prospectors and loggers worked very hard, and usually in teams, but they frequently experienced bouts of time when there was no work because of the vagaries of mountain weather or even of the global economy. Carousing was one answer to the question of what to do on days off, but the number of sports teams organized by both men and women suggest that the teamwork that was normal for them at work translated nicely to the pitch or the rink or the court when there was no work to be done.

The Sporting Life It’s no surprise that sports of all kinds were popular in Kaslo from the start. Loungers were not likely to undertake the arduous trip into Kootenay Country. The founders of Kaslo were ambitious, mostly fit, and unafraid of physical risk. Miners, prospectors and loggers worked very hard, and usually in teams, but they frequently experienced bouts of time when there was no work because of the vagaries of mountain weather or even of the global economy. Carousing was one answer to the question of what to do on days off, but the number of sports teams organized by both men and women suggest that the teamwork that was normal for them at work translated nicely to the pitch or the rink or the court when there was no work to be done.

The spirit that embraces risk takes many forms, even social and political. Within two years of having the vote in BC, in 1918 two Kaslo women ran and were elected to City Council. They haven’t been wallflowers at sport either; Kaslo ladies’ hockey players have been “socking it in the twine” for more than a century.

To this day, the sports teams of Kaslo’s children, no matter how small – boys, girls, or mixed – have competed successfully with the bigger towns in the region. Is this due to their relative isolation in a village, where they grow up knowing each other like brothers and sisters? Or is it their ancestors?

c1940

There was always a lot of talk in the town around who was the strongest man. Cecil Pangburn, who was tall and lean, or Franz Eimer whowas short and very stocky. A big crowd gathered and a mule with a pack was brought forward. The contest would be who could lift the mule’s back feet off the ground. Cecil getting under the mule could not straighten his long legs. Franz got under the mule, put his back against the belly and snapped his legs upright. The mule’s back feet came off the ground and Franz won the day.

Curling

Kaslo was the first settlement in the Kootenays to organize curling. The first curling game played in Kaslo was in 1893 – the first big bonspiel was held on Mirror Lake in 1896. At first the Kaslo Curling Club had to depend on the ice at Mirror Lake but in 1897, the Kaslo Rink Company bought 8 lots from George Kane in the area where the Kaslo Motel is now. Two curling rinks and then a skating/hockey rink shielded by rough-sawn boards were created.

Hockey

Like curling, hockey was first played on ice at Mirror Lake or any small pond in the area. In 1897 the Nelson hockey club had just organized and Kaslo players were invited to play them. Then for about 50 years the rink was at the corner of D and 4th Street, (a covered ice surface for much of that time), after that in the area where the Public Works is now, then back again to Mirror Lake until the Kaslo Recreation Complex was completed in 1975.

You gotta have ‘Wa’.

Wa is a Japanese word that means harmony. It was the sport of baseball that brought together wary townspeople and the Japanese internees who arrived in May, 1942.

A few of Kaslo’s internees used to play on the Vancouver Asahi baseball team. With their daring base running and bunting, the Asahi’s style of play led them to win five consecutive Pacific Northwest Championships between 1937 and 1941. After that year, they and their families were forcibly removed to camps and towns like Kaslo. Games and tournaments were organized between West Kootenay towns which brought many families back together briefly during that hard time.

Golf

A.J. Curle, or “Unc Curle” as he was called by the children of Kaslo, worked in the office of the Kaslo and Slocan Railway. He was also a land agent, fruit growers’ association secretary, and was on the Village Council in 1916-17. A.J is credited as the founder of the Kaslo Golf Club and was reportedly the first to own golf clubs in Kaslo.

Kaslo’s golf course was financed with a bond sale and opened for the first time in 1925. Over the years the four holes have become nine and improvements are still being made. A beautiful timber frame clubhouse was completed in 2007 and in 2017 some of the fairways were realigned to reduce the risk of golf balls being driven over to the next fairway and conking unsuspecting golfers on the head.

Still, it’s very likely that A.J. Curle would recognize the course today as the one he spearheaded almost a century ago. He would be sure to enter the Rainbow Tournament, which, along with the incredible view, has been a mainstay of the course always.

Kaslo's Firsts

When Kaslo was first incorporated in 1893, its promoters boasted that it was “the neatest wooden town in British Columbia.” Yet imagine the simmering anxiety of living in a town where every house, shack and warehouse was built of wood – especially in the wintertime when everyone was heating their rooms with open fire places and woodstoves.

Kaslo had no running water and no fire hydrants until 1896, two years after the 1894 fire that destroyed half of the buildings on Front Street. Before that, water from the Kaslo River was sold from two hogsheads on a wagon drawn by a team of horses. The cost was 25¢ a barrel to the downtown residents, while the unfortunate ones living out of the lower town had to pay double that price.

At first Kaslo’s water was piped from a dam on the Kaslo River to the reservoir, which was located where the community garden is now on 8th and Washington streets. But there were complaints about pollution from the mines upriver and in 1936, 6,000 feet of wood-stave piping was laid down through the woods to bring water from Kemp Creek to the reservoir. You can still see parts of the old wooden pipes as you walk along the Lettrari Loop of the Kaslo River Trail. In 1981 the reservoir in upper Kaslo was filled in with sawdust and a new reservoir was finished west of the airport. Although the Kemp Creek source is as pristine as one could wish for, from time to time, especially during spring runoff, it needs treatment.

In 2002 McDonald creek burst its banks and washed out the water system used by the Allen Division in upper Kaslo. Kaslo invited the residents to hook into the Village’s system which at that time was being upgraded to the tune of a million dollars – a cost borne equally by Kaslo and Area D and the provincial and federal government.

In 2002 McDonald creek burst its banks and washed out the water system used by the Allen Division in upper Kaslo. Kaslo invited the residents to hook into the Village’s system which at that time was being upgraded to the tune of a million dollars – a cost borne equally by Kaslo and Area D and the provincial and federal government.

1896 was a banner year for new technology and convenience in Kaslo. The first telephone line – with eight telephones and a fire alarm system – was installed that summer. The operator worked out of the Geigerich house, now the home of Tom and Georgie Humphries.

By Chrismastime, the first electric light was switched on. The newly built Langham Hotel was one of the first to be hooked up. An article in the Sandon Paystreak described it as “one of the most comfortable and commodious residential quarters in town, having the benefits of all modern improvements in the way of electric lights, baths, etc.”

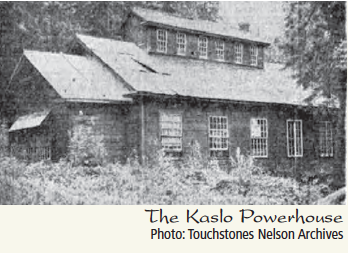

In 1914 the City of Kaslo purchased the power plant and distribution system from George Alexander for $27,500. The power system began with a 18m dam on the Kaslo River. Water traveled through wood-stave pipe to the powerhouse, where it was returned to the river. (You can see the remains of these wooden pipes still, especially obvious near the Trailblazer bridge on the River Trail.) Each home in Kaslo was provided with free electricity to power their front porch light and this practice continued until after the powerplant was bought by West Kootenay Power in 1962.

The first motion pictures were shown in 1913 in the Eagles Hall (now the Mason Hall on 3rd Street and A Avenue.) Later, movies were shown at the Drill Hall (now known as the Legion Hall) and then at the Drexall Theatre on Front Street (now Selkirk College.)

Norm McCartney recalls the first movie he ever saw. He lived out of town on the Back Road, on land now known as Lofstedt Farm but was known as the Turnip Farm when Norm was a child. He and his buddy “Tyke” MacMurphey rode all the way to the Drill Hall in Kaslo on horseback. They stabled Cherry, Norm’s horse, over in Hogan’s Alley, at the farrier’s place kitty-corner on A Avenue and 5th. Once inside the hall, after the opening cartoons and the newsreels, the dramatic action of Robin Hood began. On the screen, arrows were flying in every direction and cinematic music boomed from the loudspeakers, filling the darkened hall. Both he and Tyke were too afraid to admit to their terror so they both decided they had better go and see how the horse was doing. They spent the rest of the movie stroking Cherry’s nose.

Radio and TV came to Kaslo much later than to most Canadians. The mountains were a formidable barrier in pre-satellite days. Until the CBC was persuaded to put up a tower at Pilot Point, TV and radio signals were spotty, and came from Spokane. In the mid 1950s Bruce Tate and some friends went up and down the beach near Vimy park, holding a portable TV connected by several linked extension cords to the nearest house. They angled the TV’s antennae (“rabbit ears”) this way and that until they caught a signal. They had tuned into a western! The friends all flopped down on the sand and watched the show.

There is some dispute about who owned the first car in Kaslo. Some claim it was Fred Archer. It may have been the Caldwells in1912, whose car is pictured here. If it was ever to leave Kaslo, the car would have been loaded on the K&S Railway or into the hold of a sternwheeler.

See where to eat, sleep, play and shop in town. Also, visit www.gokootenays.com to learn more about the surrounding Kootenay areas.